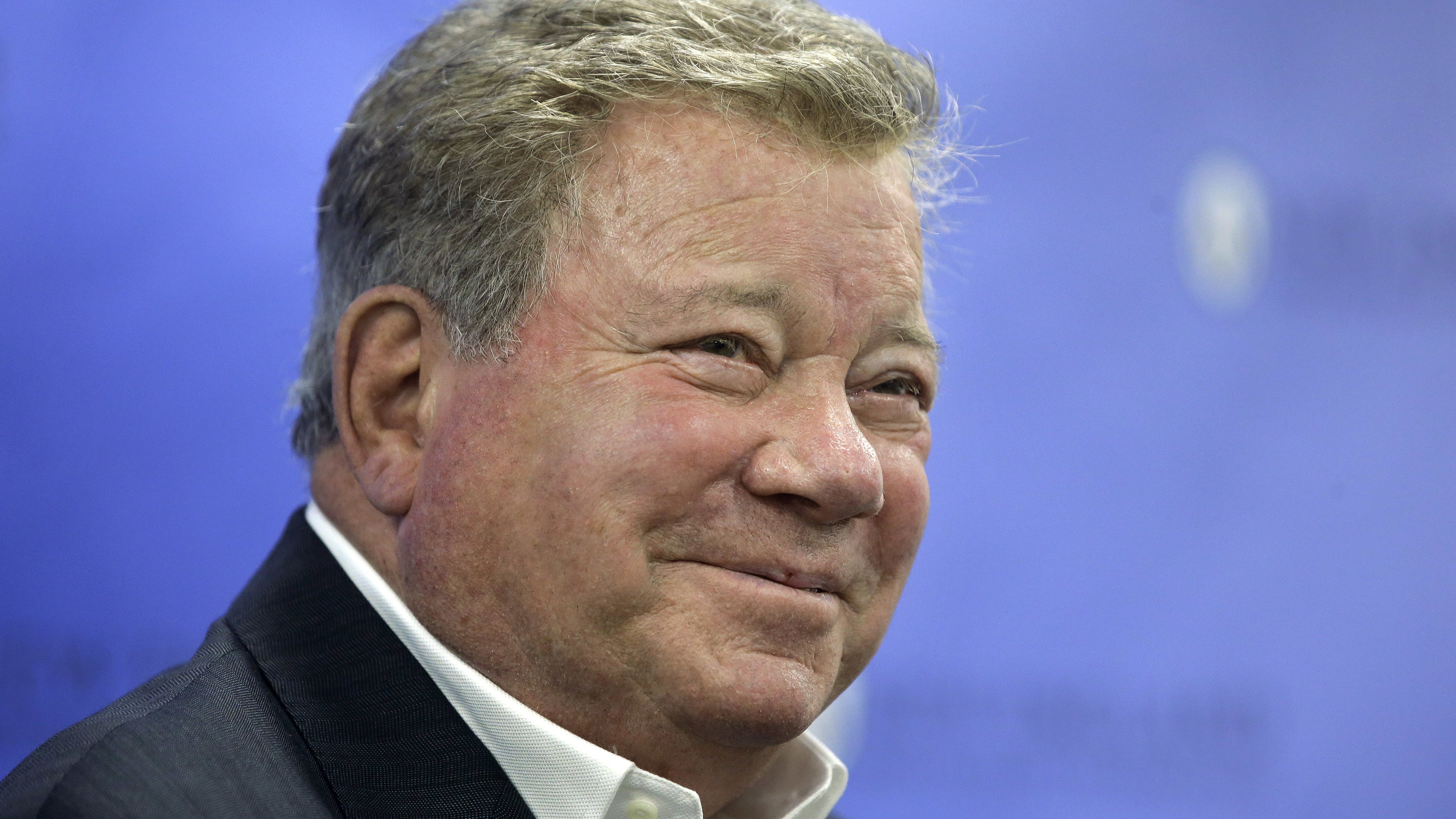

In this reflection, we delve into the extraordinary experience of William Shatner, the “Star Trek” icon, as he journeyed into space aboard Jeff Bezos’ Blue Origin space shuttle on October 13, 2021. At 90 years old, Shatner became the oldest living a person who travels to space, but his reaction to the voyage was surprisingly profound and unexpected.

Our crew consisted of myself, tech entrepreneur Glen de Vries, Blue Origin VP and former NASA International Space Station flight controller Audrey Powers, and former NASA engineer Dr. Chris Boshuizen. We underwent numerous simulations and training exercises to prepare, but nothing can truly prepare you for leaving Earth’s atmosphere! The ground crew, sensing our apprehension, continuously reassured us: “Everything’s going to be fine. Don’t worry about anything. It’s all okay.” Easy for them to say, I thought. They get to stay here on the ground.

During our preparation, we ascended the gantry eleven flights to get a sense of the rocket’s presence. Then, we were led to a reinforced concrete room with oxygen tanks. “What’s this room for?” I inquired casually.

“Oh, you guys will rush in here if the rocket explodes,” a Blue Origin member responded matter-of-factly.

Uh-huh. A safe room. Eleven stories up. In case the rocket explodes.

Well, at least they’ve thought of it.

When the day finally arrived, the Hindenburg disaster was on my mind. Not enough to back out, of course – I’m a professional, and I was booked. The show had to go on.

We settled into the pod, following a specific strapping-in sequence. I hadn’t perfected it in the simulator, so the importance of navigating weightlessness to correctly strap into the seat was at the forefront of my mind.

That, and the Hindenburg crash.

Then, a delay.

“Sorry, folks, there’s a slight anomaly in the engine. It’ll just be a few moments.”

An anomaly in the engine?! That sounds kinda serious, doesn’t it?

An anomaly is something that does not belong. What is currently in the engine that doesn’t belong there?!

More importantly, why would they tell us that? There is a time for unvarnished honesty. I get that. This wasn’t it.

William Shatner in Blue Origin space shuttle

William Shatner in Blue Origin space shuttle

Thirty seconds later, we were cleared for launch, and the countdown commenced. With immense noise, fire, and force, we lifted off. I watched Earth disappear. As we ascended, I felt the pressure, the gravitational forces pulling at me – the g-forces. An instrument indicated the g-forces we were experiencing. At two g’s, I struggled to lift my arm. At three g’s, I felt my face being pushed into my seat. I don’t know how much more of this I can take, I thought. Will I pass out? Will my face melt into a pile of mush? How many g’s can my ninety-year-old body handle?

Then, suddenly, relief. No g’s. Zero. Weightlessness. We were floating.

We released our harnesses and floated around. The others immediately began somersaulting, enjoying the effects of weightlessness. I wanted no part in that. I needed to reach the window as quickly as possible to see what was out there.

I looked down and saw the hole our spaceship had created in Earth’s thin, blue-tinged layer of oxygen. It was as if a wake trailed behind us, disappearing as soon as I noticed it.

Turning to face the other direction, I gazed into space. I love the mystery of the universe, the questions raised over millennia of exploration and hypotheses: exploding stars whose light reaches us years later, black holes absorbing energy, satellites revealing entire galaxies in seemingly empty areas. All of this has thrilled me for years. But when I looked into space, there was no mystery, no majestic awe. All I saw was death.

I saw a cold, dark, black emptiness, unlike any blackness on Earth. It was deep, enveloping, all-encompassing. I turned back toward the light of home, seeing Earth’s curvature, the beige desert, white clouds, and blue sky. It was life, nurturing, sustaining life – Mother Earth, Gaia. And I was leaving her.

Everything I had thought was wrong. Everything I had expected to see was wrong.

I had believed that going into space would provide the ultimate catharsis, strengthening my connection to all living things, and that being up there would be the next beautiful step to understanding the harmony of the universe. In the film “Contact,” when Jodie Foster’s character goes to space, she whispers in astonishment, “They should’ve sent a poet.” I had a different experience. I discovered that the beauty isn’t out there, it’s down here, with all of us. Leaving that behind made my connection to our tiny planet even more profound.

It was among the strongest feelings of grief I have ever encountered. The contrast between the vicious coldness of space and the warm nurturing of Earth below filled me with overwhelming sadness. Every day, we are confronted with the knowledge of further destruction of Earth at our hands: the extinction of animal species, of flora and fauna, things that took five billion years to evolve, and suddenly we will never see them again because of the interference of mankind. It filled me with dread. My trip to space was supposed to be a celebration; instead, it felt like a funeral.

I later learned that I was not alone in this feeling. It is called the “Overview Effect” and is common among astronauts, including Yuri Gagarin, Michael Collins, Sally Ride, and many others. Essentially, when someone travels to space and views Earth from orbit, a sense of the planet’s fragility takes hold in an ineffable, instinctive manner. Author Frank White first coined the term in 1987: “There are no borders or boundaries on our planet except those that we create in our minds or through human behaviors. All the ideas and concepts that divide us when we are on the surface begin to fade from orbit and the moon. The result is a shift in worldview, and in identity.” This feeling of the “Overview Effect” is one many experience as a person who travels to space.

It can change the way we look at the planet but also other things like countries, ethnicities, religions; it can prompt an instant reevaluation of our shared harmony and a shift in focus to all the wonderful things we have in common instead of what makes us different. It reinforced tenfold my own view on the power of our beautiful, mysterious collective human entanglement, and eventually, it returned a feeling of hope to my heart. In this insignificance we share, we have one gift that other species perhaps do not: we are aware – not only of our insignificance, but the grandeur around us that makes us insignificant. That allows us perhaps a chance to rededicate ourselves to our planet, to each other, to life and love all around us. If we seize that chance.

What does a person who travels to space truly experience? More than just the thrill of weightlessness and the stunning view, it is a profound shift in perspective, a stark realization of Earth’s fragility and the interconnectedness of all life. This experience can lead to a renewed commitment to protecting our planet and fostering greater understanding among all people. The journey of a person who travels to space can be transformative, not just for the individual, but for all of humanity.