Energy manifests in numerous forms, capable of transforming from one type to another. Potential energy is stored in sources like batteries and dams, while kinetic energy is evident in moving objects. When charged particles, such as electrons and protons, accelerate, they generate electromagnetic fields. These dynamic fields are responsible for transporting electromagnetic radiation, commonly known as light.

Ripples expanding on the surface of water, illustrating wave propagation.

Ripples expanding on the surface of water, illustrating wave propagation.

Contrasting Electromagnetic and Mechanical Waves

Energy transmission occurs primarily through two wave types: mechanical and electromagnetic. Water waves and sound waves exemplify mechanical waves, which arise from disturbances or vibrations within matter—whether solid, liquid, gas, or plasma. The medium through which these waves travel is crucial for their propagation. For instance, water waves are generated by vibrations in water, and sound waves by vibrations in air. Mechanical waves propagate by causing molecules within the medium to collide and transfer energy, similar to a domino effect. Crucially, mechanical waves like sound cannot travel through the vacuum of space because they necessitate a medium for transmission.

Classical wave motion involves energy transfer without the bulk transport of matter. Consider ripples on a pond; they transmit energy across the water, but the water molecules themselves largely remain in place, much like a bobbing bug on the water’s surface.

The Nature of Electromagnetic Waves

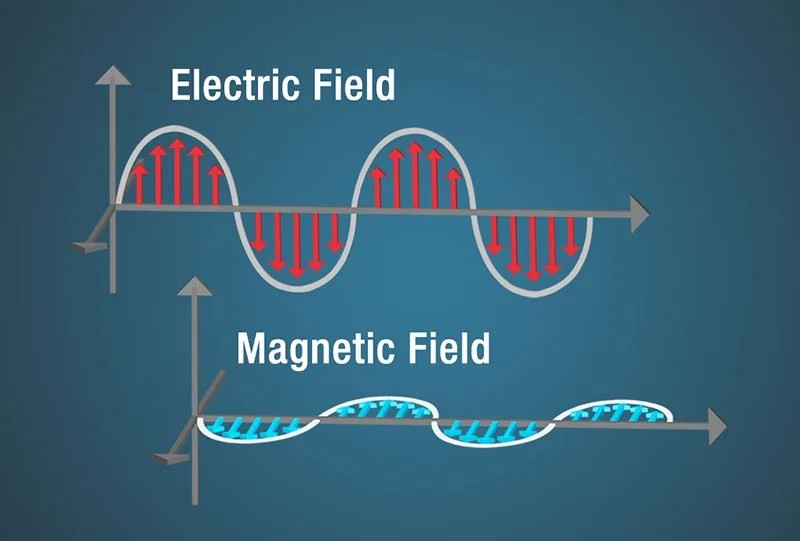

Electricity can be static, such as the charge that causes hair to stand on end. Magnetism can also be static, as seen in refrigerator magnets. However, a changing magnetic field induces a changing electric field, and vice versa—these two phenomena are inherently linked. This dynamic interplay of electric and magnetic fields gives rise to electromagnetic waves. A key distinction between electromagnetic and mechanical waves is that electromagnetic waves do not require a medium to propagate. This unique property allows electromagnetic waves to travel not only through air and solids but also through the vacuum of space.

In the mid-19th century, Scottish scientist James Clerk Maxwell formulated a groundbreaking theory explaining electromagnetic waves. He theorized, and later experiments confirmed, that oscillating electric and magnetic fields could couple to form these waves. Maxwell encapsulated the relationship between electricity and magnetism in a set of equations now known as “Maxwell’s Equations.” These equations are fundamental to our understanding of how electromagnetic waves are formed and propagate.

Diagram illustrating electric and magnetic fields oscillating perpendicularly in an electromagnetic wave.

Diagram illustrating electric and magnetic fields oscillating perpendicularly in an electromagnetic wave.

Heinrich Hertz, a German physicist, experimentally validated Maxwell’s theories by producing and detecting radio waves. He demonstrated that radio waves travel at the speed of light, confirming that radio waves are indeed a form of light and a type of electromagnetic wave. Hertz also discovered how to generate electromagnetic waves by detaching electric and magnetic fields from wires, allowing them to propagate freely through space as Maxwell predicted. The unit of frequency, “hertz” (Hz), denoting cycles per second, is named in his honor.

Wave-Particle Duality: Light’s Ambiguous Nature

Light exhibits a dual nature, behaving as both waves and particles. It is composed of discrete energy packets called photons. Photons are massless, carry momentum, and travel at the speed of light. The experimental setup determines whether the wave-like or particle-like properties of light are observed. For example, using a diffraction grating to separate light into a spectrum demonstrates its wave-like nature. Conversely, digital camera detectors reveal light’s particle nature, where individual photons liberate electrons, enabling image detection and storage.

Polarization: Aligning Electromagnetic Fields

Polarization is a fundamental property of light and other electromagnetic waves, describing the alignment of the electromagnetic field’s oscillations. In linearly polarized light, like in the diagram above depicting the electric field in red, the oscillations occur along a single plane. Imagine throwing a Frisbee at a picket fence; it will pass through if aligned correctly but be blocked if rotated. Similarly, polarizing sunglasses reduce glare by selectively absorbing polarized light, typically horizontally polarized light reflected from surfaces.

Describing Electromagnetic Energy: Frequency, Wavelength, and Energy

The terms light, electromagnetic waves, and electromagnetic radiation are interchangeable, all referring to electromagnetic energy. This energy can be characterized by its frequency, wavelength, or energy level. These parameters are mathematically interconnected, meaning knowing one allows calculation of the others. Radio waves and microwaves are commonly described by frequency (Hertz), infrared and visible light by wavelength (meters), and X-rays and gamma rays by energy (electron volts). This convention ensures convenient use of units, avoiding excessively large or small numbers.

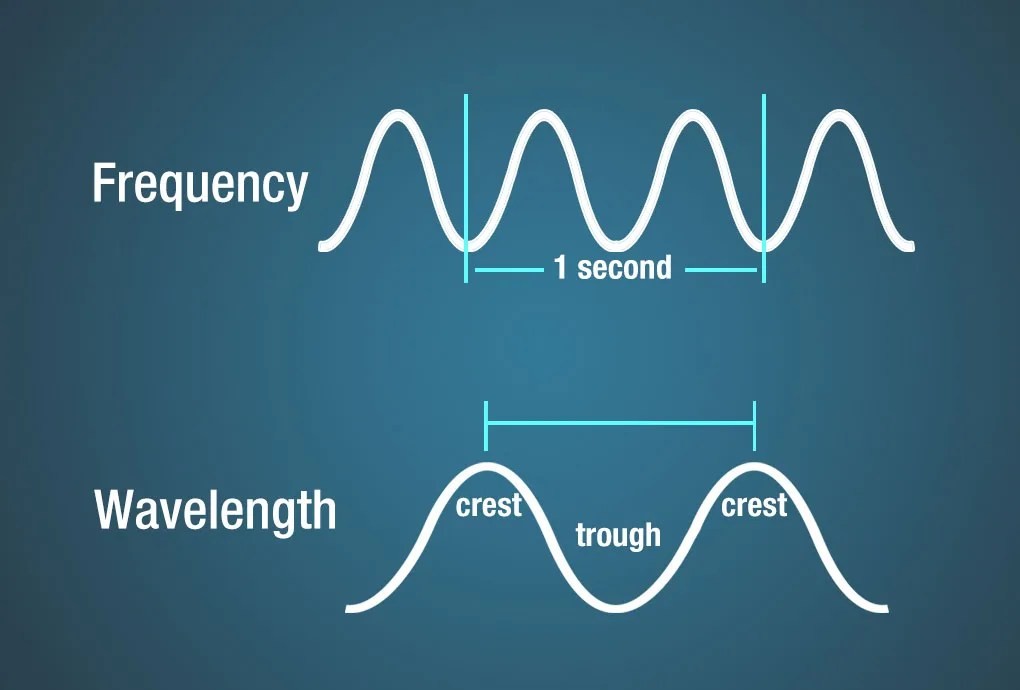

Frequency: Cycles Per Second

Frequency quantifies how many wave crests pass a fixed point per second. One cycle per second is defined as one Hertz (Hz), named after Heinrich Hertz. A wave completing two cycles per second has a frequency of 2 Hz. Higher frequency means more energy, and often corresponds to different types of electromagnetic radiation within the spectrum.

Wavelength: Distance Between Crests

Diagram illustrating wavelength as the distance between successive crests of a wave and frequency as the number of crests passing a point per second.

Diagram illustrating wavelength as the distance between successive crests of a wave and frequency as the number of crests passing a point per second.

Electromagnetic waves, similar to ocean waves, possess crests and troughs. Wavelength is the distance between two consecutive crests. The electromagnetic spectrum spans an enormous range of wavelengths, from extremely short wavelengths, smaller than atoms, to extremely long wavelengths, exceeding the diameter of Earth. Different wavelengths correspond to different types of electromagnetic radiation, from radio waves to gamma rays.

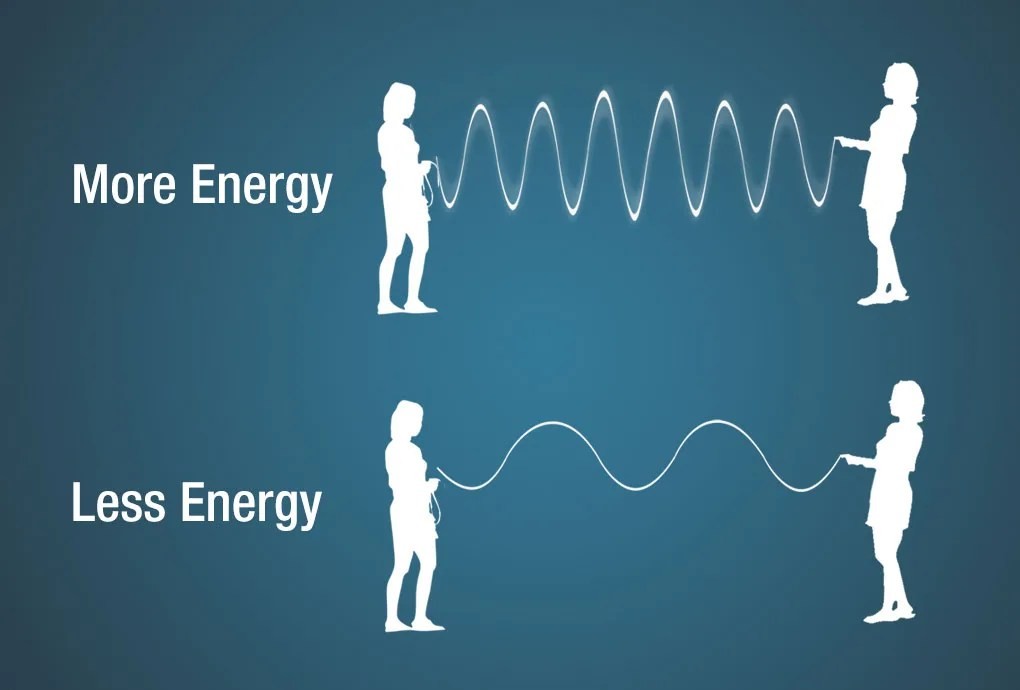

Energy: Electron Volts and Wave Intensity

Illustration showing the relationship between wave energy, frequency, and wavelength using a jump rope analogy.

Illustration showing the relationship between wave energy, frequency, and wavelength using a jump rope analogy.

Electromagnetic wave energy is also quantified in electron volts (eV). One electron volt represents the kinetic energy gained by an electron moving through a potential difference of one volt. As you move along the electromagnetic spectrum from longer to shorter wavelengths, the energy increases. Imagine a jump rope; more energy is required to create more waves (higher frequency, shorter wavelength) in the rope. Higher energy electromagnetic waves, like gamma rays, have shorter wavelengths and higher frequencies, while lower energy waves, like radio waves, have longer wavelengths and lower frequencies.

Next: Wave Behaviors

Citation

APA

National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Science Mission Directorate. (2010). Anatomy of an Electromagnetic Wave. Retrieved [insert date – e.g. August 10, 2016], from NASA Science website: http://science.nasa.gov/ems/02_anatomy

MLA

Science Mission Directorate. “Anatomy of an Electromagnetic Wave” NASA Science. 2010. National Aeronautics and Space Administration. [insert date – e.g. 10 Aug. 2016] http://science.nasa.gov/ems/02_anatomy

Keep Exploring

Discover More Topics From NASA

[

James Webb Space Telescope

Webb is the premier observatory of the next decade, serving thousands of astronomers worldwide. It studies every phase in the…

](https://science.nasa.gov/james-webb-space-telescope/) [

Perseverance Rover

This rover and its aerial sidekick were assigned to study the geology of Mars and seek signs of ancient microbial…

](https://science.nasa.gov/perseverance-rover/) [

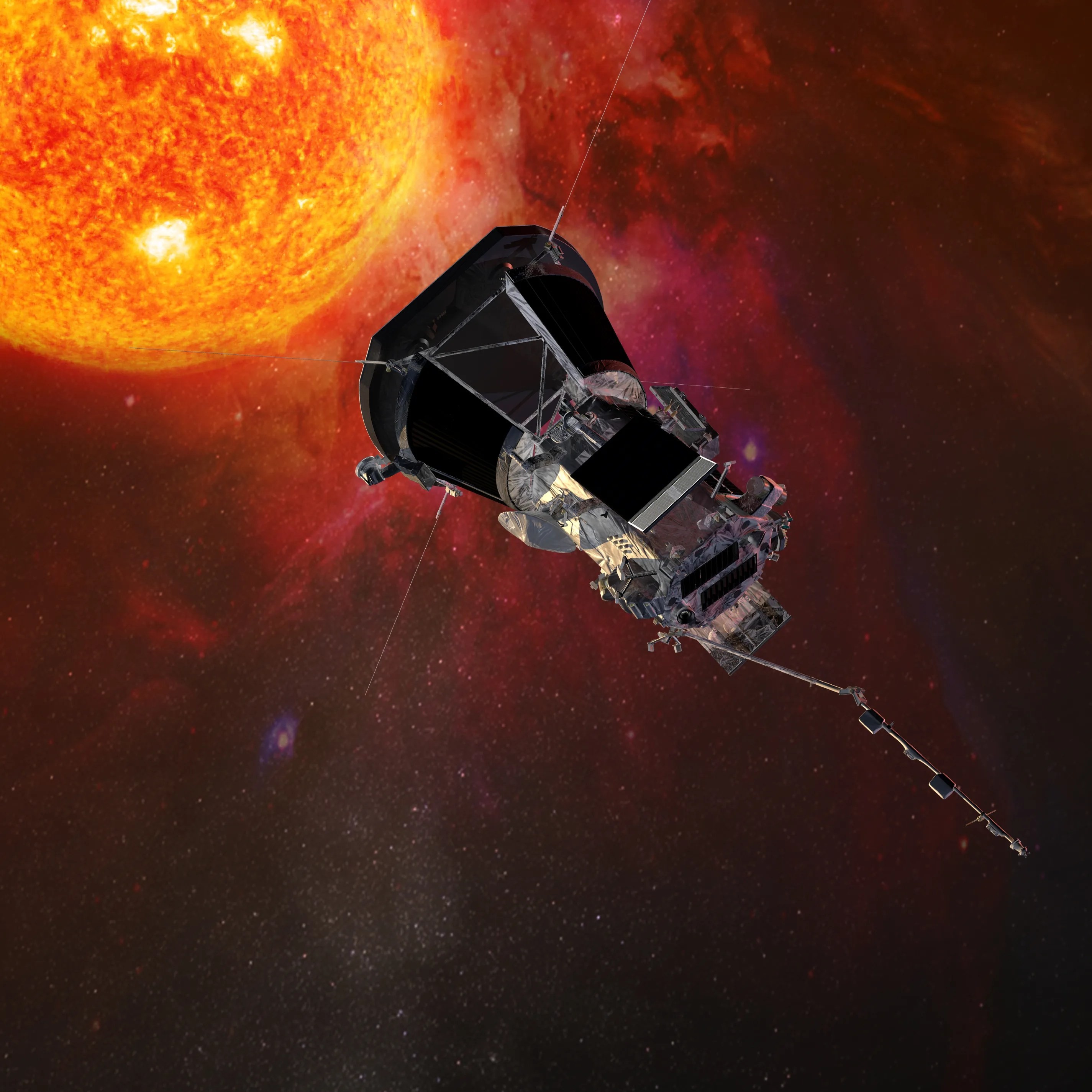

Parker Solar Probe

On a mission to “touch the Sun,” NASA’s Parker Solar Probe became the first spacecraft to fly through the corona…

](https://science.nasa.gov/parker-solar-probe/) [

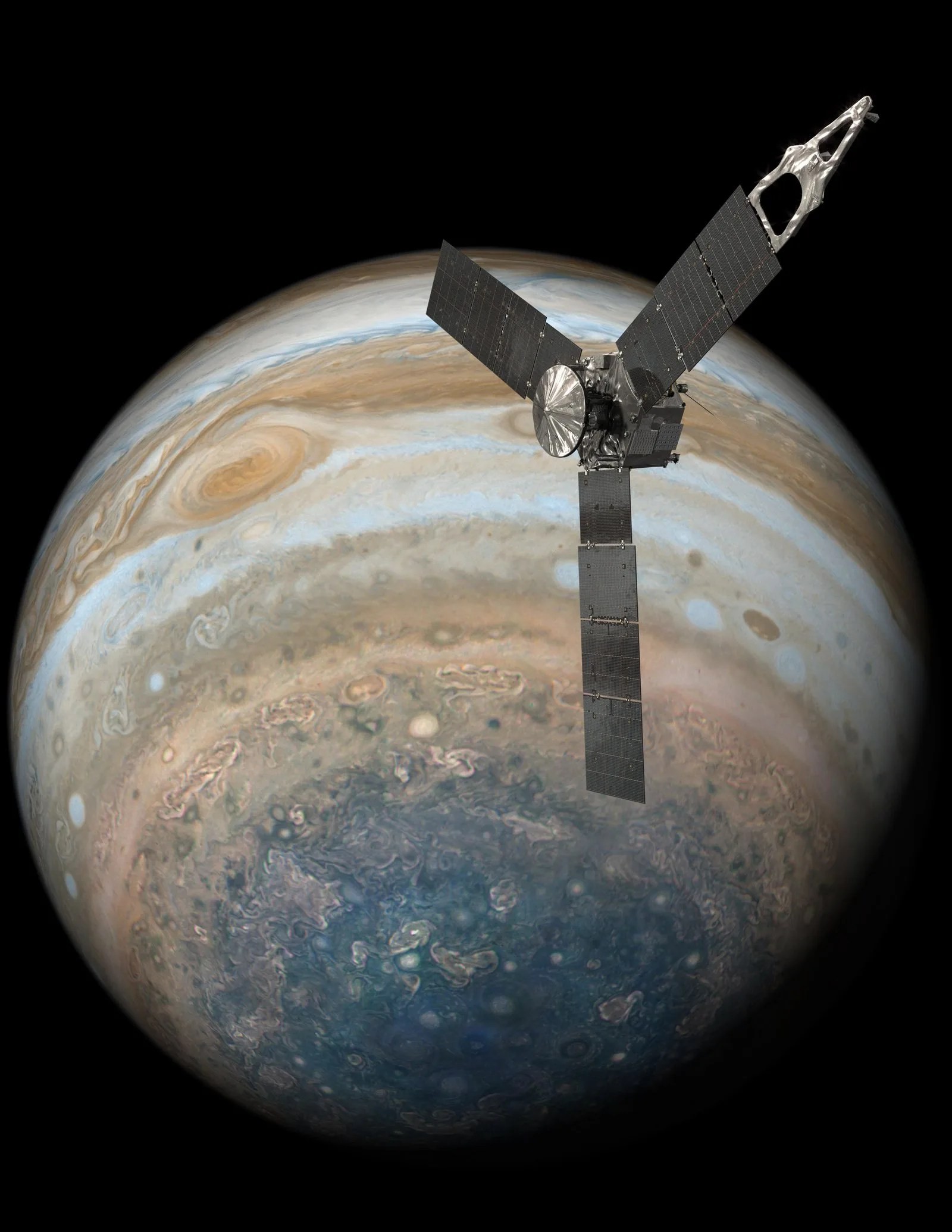

Juno

NASA’s Juno spacecraft entered orbit around Jupiter in 2016, the first explorer to peer below the planet’s dense clouds to…

](https://science.nasa.gov/juno/)