Birds embarking on their long journeys south in distinctive V-shaped formations – this iconic imagery perfectly encapsulates migration, the regular, large-scale movement of birds between their breeding grounds in the summer and their winter habitats. However, geese are just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to avian travelers. Astonishingly, over half of the 650+ bird species that breed in North America are migratory. But What Do Birds Travel In, and why do they undertake these incredible journeys?

Flock of Canada Geese in V formation, a classic example of bird migration.

Flock of Canada Geese in V formation, a classic example of bird migration.

The Driving Force Behind Bird Migration: Why Do Birds Migrate?

While the idea of escaping the cold might spring to mind, the primary motivation for bird migration is overwhelmingly the search for food. As Dr. Kevin McGowan from the Cornell Lab of Ornithology explains, migration is “almost always about finding food.” While some birds, like chickadees in boreal forests, can endure winter by finding dormant insects, many others rely on flying or moving insects, which become scarce in colder regions. Birds can withstand cold temperatures, but the dwindling food supply in certain habitats necessitates their seasonal relocation.

[soundscape of birds calling]

The Trigger: What Prompts Birds to Start Migrating?

The signal for migration isn’t a sudden drop in temperature, but rather the subtle shift in daylight hours. These changes act as a “proximate mechanism,” initiating hormonal changes in birds and preparing them for the journey. Birds are remarkably sensitive to even minor variations in daylight length. This internal prompting is known as Zugunruhe, or migratory restlessness. Even in captivity, as daylight changes, migratory birds exhibit this restlessness, an innate urge to move and journey onwards.

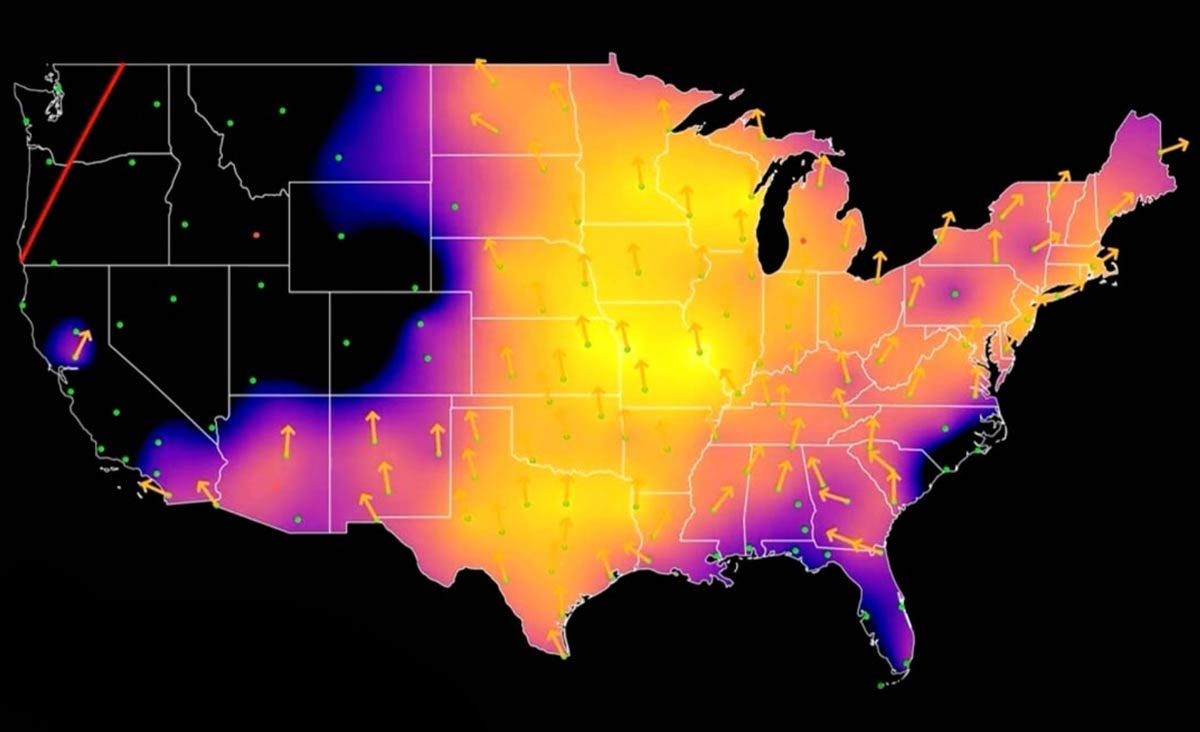

[Image: map of continental United States showcasing predicted bird migration intensity with color scale.]

Migration Timing: How Variable is Bird Travel?

Bird migration timing can be remarkably precise for some species. For instance, the arrival of Red-winged Blackbirds in central New York is consistently within a two-week window each year. However, migration isn’t a rigid schedule. Individual bird migration can be influenced by real-time factors like weather patterns and local conditions, leading to fine-tuning of their travel plans. So, while there’s predictability, flexibility is also key.

Migration Groups: Do Adult and Juvenile Birds Travel Together?

Migration isn’t a uniform mass movement. Different groups within bird populations often travel separately. Typically, breeding males lead the way south, departing before females and juveniles. Adults generally migrate ahead of juveniles. This staggered departure might be because younger birds require more time to build up fat reserves necessary for the energy-demanding migration. These distinct travel patterns highlight the complexity of bird migration strategies.

Daytime vs. Nighttime Travel: When Do Birds Migrate?

Contrary to what many might assume, the majority of bird migration occurs at night. Several factors contribute to this nocturnal preference. Nighttime offers fewer predators, and since foraging is limited in darkness, birds can dedicate this time to flying. Furthermore, nighttime flight allows birds to tap into a unique navigational tool: the Earth’s magnetic field.

[Image: graphic of a Yellow Warbler flying against a globe depicting magnetic field lines.]

Birds possess the incredible ability to sense magnetic fields when light is limited. This “magnetic sense” acts as an internal compass, enabling them to discern north and south even in the dark. This remarkable adaptation explains why many birds choose to travel under the cover of night, utilizing the Earth’s magnetic field for guidance.

Helping Migratory Birds: How Can We Assist Avian Travelers?

While we can’t alter a bird’s migratory path, we can provide crucial support. Hummingbird feeders offer a readily available energy source for these tiny migrants. Keeping feeders out until it gets cold provides sustained assistance. Suet feeders are beneficial for other bird species. A significant way to help, particularly in urban areas, is to reduce light pollution by turning off unnecessary lights at night. Artificial lights can disorient migrating birds, especially in cities. Planting native plants also provides natural food sources and habitats. These simple actions can collectively make a positive difference for migrating birds.

[soundscape of bird calls ends]

Birds migrate to bridge the gap between periods of resource scarcity and abundance. The primary resources driving these journeys are food and suitable nesting sites. In the Northern Hemisphere, spring migration north coincides with the explosion of insect populations, burgeoning plant life, and ample nesting opportunities. As winter approaches, and these resources dwindle, birds journey south again. While escaping cold is a factor, the availability of food is the paramount driver.

Diverse Journeys: Types of Bird Migration

Migration, in essence, is the periodic, large-scale movement of animal populations. One way to categorize migration is by the distance covered. While migration patterns can vary within each category, short and medium-distance migrations exhibit the most variability. Long-distance migrations, while incredibly demanding, are undertaken by around 350 North American bird species.

Northern Cardinal perched on a branch, representing permanent resident birds.

Northern Cardinal perched on a branch, representing permanent resident birds.

Permanent residents are birds that forgo migration altogether. They have adapted to find sufficient food sources year-round within their established territories.

Northern Bobwhite quail standing in grassy habitat, representing short-distance migrants.

Northern Bobwhite quail standing in grassy habitat, representing short-distance migrants.

Short-distance migrants undertake relatively minor movements, often altitudinal shifts, such as moving from higher to lower elevations on mountainsides to find food or shelter.

Blue Jay perched on a branch, representing medium-distance migrants.

Blue Jay perched on a branch, representing medium-distance migrants.

Medium-distance migrants travel hundreds of miles, often within the same continent, seeking milder climates and consistent food availability.

Magnolia Warbler perched on a branch, representing long-distance migrants.

Magnolia Warbler perched on a branch, representing long-distance migrants.

Long-distance migrants embark on epic journeys, typically breeding in the United States and Canada and wintering as far south as Central and South America.

Unraveling the Origins of Long-Distance Migration

While short-distance migration likely arose from straightforward food-seeking needs, the development of long-distance migration patterns is a far more intricate evolutionary story. These patterns have evolved over millennia and are partly governed by a bird’s genetic makeup, alongside responses to weather, geography, food sources, and daylight duration.

For birds that spend winters in the tropics, migrating north for breeding seems counterintuitive. One theory suggests that the tropical ancestors of these birds gradually expanded northward from their tropical breeding grounds over generations. The seasonal surge in insect food and extended daylight hours in northern regions allowed them to raise larger broods (4–6 chicks on average) compared to their tropical counterparts (2–3 chicks). As glacial retreats expanded breeding zones northward, these birds maintained their ancestral link to tropical wintering grounds, returning south as winter conditions and dwindling food supplies made northern life harsher. Supporting this theory is the tropical origin of many North American vireos, flycatchers, tanagers, warblers, orioles, and swallows.

BirdCast: Real-Time Migration Tracking

Map of the continental U.S. showing bird migration intensity in 2021, visualized by BirdCast.

Map of the continental U.S. showing bird migration intensity in 2021, visualized by BirdCast.

Want to know when, where, and how intensely birds are migrating? The BirdCast program provides answers by utilizing radar technology to generate real-time maps of nocturnal bird migration. It even offers 3-day migration forecasts, predicting peak migration nights. This information is invaluable for conservation efforts, aiding decisions like wind turbine placement to minimize bird collisions. By forecasting high-migration nights, cities can implement “lights out” initiatives, dimming building lights to prevent fatal collisions for millions of birds. BirdCast data also empowers researchers to study migration behavior, understand how climate change impacts migration patterns, and investigate the link between migration timing and bird population fluctuations.

Migration Triggers: What Sets Birds in Motion?

The precise mechanisms that initiate migration are complex and not fully understood, varying among species. Migration is likely triggered by a combination of cues: changes in day length, decreasing temperatures, shifts in food availability, and an underlying genetic predisposition. For centuries, bird keepers observed “zugunruhe” in caged migratory birds each spring and fall – a restless fluttering in the direction of their migratory route. Even within the same species, different populations may exhibit variations in migratory patterns.

Navigation Masters: How Do Birds Find Their Way?

Migratory birds display astonishing navigational prowess, often covering thousands of miles annually, retracing the same routes year after year with remarkable accuracy. Incredibly, first-year birds often undertake their initial migration solo, instinctively finding their wintering grounds without prior experience, and returning to their birthplace the following spring. Their navigational secrets are still being unraveled, but it’s clear birds employ a suite of sensory tools. They utilize the sun, stars, and Earth’s magnetic field for compass information. Landmarks and the position of the setting sun also provide directional cues. Intriguingly, even the sense of smell may play a role, at least in some species like homing pigeons.

Waterfowl and cranes often follow established flyways – preferred migration routes often linked to critical stopover locations that provide essential food resources. Smaller birds tend to migrate across broader fronts. However, eBird data analysis reveals that many smaller birds adopt different routes in spring and fall, strategically leveraging seasonal weather patterns and food availability during their long journeys.

Migration Hazards: The Perils of the Journey

Migration, especially long-distance travel, is fraught with dangers. The sheer physical exertion, coupled with potential food shortages en route, adverse weather, and heightened predator exposure, makes it a grueling undertaking. In recent times, tall communication towers and buildings pose a growing threat. Attracted by artificial lights, millions of birds perish annually in collisions with these structures. Organizations like the Fatal Light Awareness Program (FLAP) and BirdCast’s Lights Out initiative are working to address this problem.

Studying Migration: Unlocking the Secrets

Scientists employ various techniques to study bird migration, including banding, satellite tracking, and geolocators – lightweight devices that record location data. A key goal is to pinpoint vital stopover and wintering locations to implement effective conservation strategies. For example, Nebraska’s Platte River serves as a crucial staging habitat for hundreds of thousands of Sandhill Cranes and endangered Whooping Cranes during their northward migration. Protecting these key locations is paramount for migratory bird conservation.

Migrant Traps: Havens for Weary Travelers

Illustration of a live oak tree teeming with various songbirds, a typical migrant trap scene.

Illustration of a live oak tree teeming with various songbirds, a typical migrant trap scene.

Certain locations act as “migrant traps,” concentrating migrating birds in unusually high numbers, often becoming renowned birding hotspots. This phenomenon arises from a combination of local weather, abundant food, or unique topography. For instance, songbirds migrating north across the Gulf of Mexico can become exhausted by headwinds. Upon reaching the Gulf Coast, they seek immediate refuge in areas offering food and shelter, often live-oak groves on barrier islands. These groves can experience “fallouts,” with massive influxes of migrants. Peninsulas also function as migrant traps, channeling birds as they follow the land before venturing over water. This explains the migration hotspot status of places like Point Pelee, Ontario; the Florida Keys; Point Reyes, California; and Cape May, New Jersey. Backyard bird feeders can become mini-migrant traps during spring migration, attracting unexpected species with diverse food, water, and natural plantings.

Range Maps: Predicting Bird Presence

Range maps in field guides are valuable tools to ascertain if and when a particular bird species might be present in your area, especially for migratory birds. However, range maps have limitations. Bird ranges can fluctuate annually, as seen with irruptive species. Ranges can also expand or contract faster than field guide updates can reflect. Digital, data-driven range maps are addressing these limitations. Powered by vast eBird observations from birdwatchers globally, “Big Data” analysis enables scientists to create animated maps showing species’ movements across continents throughout the year, revealing broader migration patterns.

Further Exploration

Bird migration is a captivating field of study with much still to be discovered. “Songbird Journeys” by Miyoko Chu from the Cornell Lab offers an engaging and accessible exploration of migration. The Cornell Lab’s Handbook of Bird Biology provides even more in-depth information on this remarkable phenomenon.

Explore Bird Migration Further

All About Birds: Your Free Bird Resource

Sustained by donations from individuals like you.