Osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures (VCFs) represent a significant health challenge, affecting a substantial portion of the population and leading to considerable morbidity. Like navigating a complex travel itinerary, understanding and managing these fractures requires expert guidance. Consider this article your “Proglity Travel Agent Login” – your gateway to comprehensive information on osteoporotic VCFs, designed to provide a clear and insightful journey through the condition, its management, and the latest treatment options.

Osteoporosis, a systemic skeletal disorder characterized by weakened bones, low bone mass, and disrupted bone structure, elevates the risk of fractures. Defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as a bone mineral density (BMD) at the hip or lumbar spine more than 2.5 standard deviations below the young normal adult reference population, osteoporosis stands as the most prevalent bone disease in the United States, posing a major public health concern. Over 10 million Americans, predominantly women, suffer from osteoporosis, with an additional 33.6 million exhibiting low BMD.1 Projections indicate a rise in osteoporosis prevalence to 14 million individuals by 2020.2 Just as a travel agent helps plan for the future, understanding these projections is crucial for healthcare planning.

Vertebral fractures emerge as the most common osteoporotic fracture in postmenopausal women. Annually, an estimated 550,000 to 700,000 osteoporotic VCFs occur, constituting approximately 27% of all osteoporotic fractures in both genders.2,3 Accurate quantification of incidence remains challenging, as only 23% to 33% of these fractures manifest clinically.4

The economic repercussions are substantial and on the rise. Direct medical costs attributed to osteoporosis in the U.S. range from $13.7 to $20.3 billion, with osteoporotic VCFs accounting for around $1.1 billion. Projections for 2025 anticipate a near 50% surge in annual overall fractures and associated costs.2 The true economic burden extends far beyond direct costs, encompassing indirect costs of disability, including lost work time, pain management, reduced mobility, sleep disturbances, and depression. Vertebral compression fractures in individuals over 45 years of age contribute to 150,000 hospital admissions, 161,000 physician office visits, and over 5 million restricted activity days annually in the United States.5 Just as you might use a “proglity travel agent login” to track travel expenses, healthcare systems must grapple with these escalating costs.

PATHOGENESIS OF OSTEOPOROTIC VERTEBRAL COMPRESSION FRACTURE

Bone structure comprises a cortical shell and a metabolically active trabecular core. Bone remodeling is a continuous equilibrium between bone formation and resorption. Peak bone mass is typically attained between ages 25 and 30.1 Subsequently, a steady bone loss of 3% to 5% per decade ensues.6 This bone loss leads to a diminished quantity of trabecular plates, resulting in a weakened skeletal framework, heightened bone fragility, and increased fracture susceptibility.7 Trabecular thinning and bone loss are age-related processes in both sexes, but more pronounced in women.8 Within the initial decade post-menopause, bone loss in the lumbar spine nearly triples in women.9 Secondary factors, such as prolonged steroid use, can also accelerate bone resorption by osteoclasts. Osteoporotic VCFs occur when axial and bending forces on the spine exceed the vertebral body’s structural integrity.10 Understanding this pathogenesis is like using your “proglity travel agent login” to access the root causes of travel delays, enabling better planning and mitigation.

RISK FACTORS FOR OSTEOPOROTIC VERTEBRAL COMPRESSION FRACTURE

Low BMD is strongly correlated with an elevated risk of vertebral fracture.11 For every standard deviation decrease from the average BMD, the risk of vertebral fracture escalates more than fourfold.12 Age also significantly contributes to osteoporotic VCF risk. Ten percent of white women aged 50 to 54 and 50% of women aged 80 to 84 have experienced at least one vertebral fracture.13 With advancing age, each 5-year increment can double the vertebral fracture risk.12

A prior fracture is a strong predictor of future fracture risk, independent of BMD, increasing the risk fivefold.13 The combination of prevalent fractures and low BMD further amplifies this risk. For each standard deviation reduction in baseline BMD below the young healthy population mean, the fracture risk within the first year following an incident fracture increases by 60%.4 The absolute risk of vertebral fractures exceeds 50% in women with both a history of fracture and BMD in the osteoporotic range.11

Fracture prevalence and incidence peak at T7–8 in the upper thoracolumbar spine and T12-L1 in the lower spine.13 Additional risk factors for a first vertebral fracture encompass smoking, low body mass index (BMI), limited daily physical activity, falls, and insufficient calcium intake during periods of high calcium demand (pregnancy or adolescence).14 Identifying these risk factors is like a “proglity travel agent login” providing access to travel advisories, helping individuals make informed decisions to minimize risks.

OSTEOPOROTIC VERTEBRAL COMPRESSION FRACTURE CHARACTERISTICS

Osteoporotic VCFs can be asymptomatic radiographic findings or symptomatic clinical events. VCFs resulting from severe trauma, such as falls from height, are almost always symptomatic. However, not all VCFs caused by minimal to moderate trauma elicit back pain.15 Many osteoporotic VCFs occur spontaneously or during routine activities like sneezing or twisting.

Similar to how not all travel logins provide the same level of access, not all osteoporotic VCFs cause pain, and the pain’s intensity and duration vary significantly. Lyritis et al. investigated the natural course of VCFs in 210 postmenopausal women with painful osteoporotic VCFs and identified two distinct types.16 Type I fractures were radiographically evident, characterized by a single episode of severe, acute pain lasting 4 to 8 weeks. Type II fractures, however, were not initially clear radiographically, but a wedge deformity gradually developed over months. Pain in type II fractures was less intense and of shorter duration than type I, but recurrent pain episodes occurred after 6 to 16 weeks and often persisted for 6 to 18 months. Women with type I fractures exhibited lower BMD compared to those with type II.16

Acute osteoporotic VCF pain is typically described as intense, deep, and localized to the fracture site, often lasting 2 weeks to 3 months. Prolonged sitting, standing, bending, and movement exacerbate the pain, while rest, lying down, heat, and distraction may offer relief. Paraspinal muscle spasm and ligament tenderness are common and may extend beyond the fracture site. Nerve root irritation or compression from the fracture can cause pain radiating along the rib cage with thoracic VCFs or into the buttocks or legs with lumbar VCFs. Spinal cord compression and myelopathy are rare in osteoporotic VCFs, more commonly associated with vertebral metastases.17,18

Chronic pain can develop following VCFs, sometimes after an asymptomatic period. The exact cause of chronic pain is unclear, but likely involves factors such as accentuated kyphosis, paraspinal muscle fatigue and spasm, neural irritation, facet joint arthroses, and physical deconditioning. The risk of chronic pain increases with the number of fractured vertebrae.6

CONSEQUENCES OF OSTEOPOROTIC VERTEBRAL COMPRESSION FRACTURE

Osteoporotic VCFs carry substantial morbidity. Patients experience diminished quality of life, difficulties in daily activities, loss of independence, depression, low self-esteem, impaired gait, balance issues, and increased mortality rates.15,19,20,21,22 Vertebral height loss and progressive kyphosis, particularly in those with multiple VCFs, lead to reduced thoracic and abdominal cavity volumes, resulting in compromised pulmonary function and early satiety, respectively.15,19 Even individuals with asymptomatic osteoporotic VCFs or non-smokers may experience pulmonary function decline due to increased kyphotic deformity.23,24,25 Asymptomatic osteoporotic VCFs are also linked to decreased quality of life, increased hospitalization, and higher mortality.26,27

Multiple studies indicate increased mortality associated with osteoporotic VCFs.20,26,28,29 A study of 6,459 women with low bone mass aged 55 to 81 revealed a 1.5-fold increased death risk in women with prevalent osteoporotic VCFs compared to those without vertebral deformities.26 A European cohort study of 6,480 men and women aged 50 to 79 reported adjusted mortality rate ratios of 1.6 for women and 1.2 for men with vertebral deformities compared to those without. 29 Mortality risk also escalated with an increasing number of osteoporotic VCFs; women with three or more vertebral deformities faced a fourfold higher mortality risk compared to those without deformities.26 Accessing this kind of data is like using a “proglity travel agent login” to understand the full scope of travel risks and plan accordingly for health and safety.

IMAGING

Initial evaluation of back pain often involves plain radiographs of the spine in lateral and anteroposterior (AP) projections. Plain radiographs can assess height loss and deformity progression over time. Prior images aid in determining if a fracture is acute, though precise fracture age can be challenging to ascertain. Osteopenic or osteoporotic bone can make subtle fractures difficult to detect.

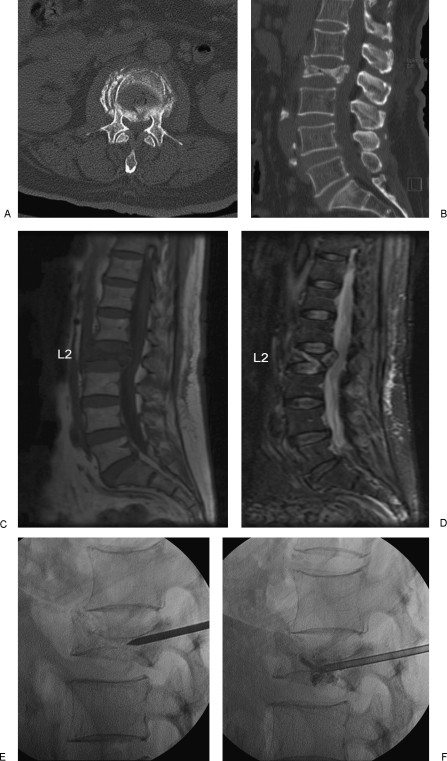

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) distinguishes between acute, subacute, and healed osteoporotic VCFs and enables assessment of the spinal canal, retropulsed fragments, and spinal cord compression. MRI can also identify other causes of back pain, such as malignancy or spinal stenosis. Acute fractures exhibit low signal intensity on T1-weighted sequences and high signal intensity on heavily T2-weighted sequences like STIR (short tau inversion recovery) (Fig. 1). Complete marrow replacement, posterior element involvement, and/or associated epidural or paraspinal masses suggest malignancy, but these findings are not definitive and may occur with benign fractures. Biopsy can be performed during vertebral augmentation if tumor is suspected.

Figure 1.

A 71-year-old female with osteoporosis and intractable back pain after a fall. (A) Axial CT image and sagittally reconstructed image (B) demonstrates a severe L2 vertebral compression fracture with retropulsion into the spinal canal. Note that the fracture does not extend into the pedicles. Abnormal marrow signal representing edema is hypointense on the T1-weighted (C) and hyperintense on the short tau inversion recovery (STIR) (D) MR images. (E,F) Unipedicular approach with careful placement of the vertebroplasty needle and injection of polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA) under biplane fluoroscopic guidance.

Computed tomography (CT) and bone scans are alternative imaging modalities for patients unsuitable for MRI. CT excels at evaluating posterior vertebral body wall integrity and suspected pedicle or posterior element fractures (Fig. 1). This information guides needle path determination during procedures. Bone scans exhibit high sensitivity but low specificity for vertebral fractures and can remain positive for over a year post-healing (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Figure 2

Figure 2

Tc-99m-labeled radionuclide bone scan (posterior view) shows increased radiotracer uptake secondary to an upper lumbar vertebral compression fracture (white arrow) and multiple left rib fractures.

CONSERVATIVE THERAPY

Conservative treatment for osteoporotic VCFs includes narcotics, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), bed rest, external bracing, physical therapy/exercise, and medical management of osteoporosis. Radicular pain may benefit from nerve root blocks or epidural steroid/anesthetic injections. Medications targeting neurogenic pain, such as antidepressants, anticonvulsants, and α-2 agonists, can be helpful for chronic pain.30 Osteoporosis treatments like hormone replacement therapy, calcitonin, bisphosphonates, raloxifene, and Teriparatide may alleviate pain by reducing fracture risk.31 Calcitonin, intravenous bisphosphonates, and Teriparatide may also directly relieve bone pain.17

Spinal orthoses or braces can reduce pain by limiting motion, decreasing postural flexion, and providing axial support for patients with muscle fatigue and spasm. Physical therapy improves body mechanics and posture, potentially reducing pain. Exercise can enhance muscle strength, flexibility, and balance, maintain BMD, and decrease the incidence of future osteoporotic VCFs.30,32 Choosing the right therapy is like using a “proglity travel agent login” to access various travel packages, comparing options to find the best fit for individual needs and circumstances.

COMPLICATIONS OF CONSERVATIVE THERAPY

While narcotics can be necessary for VCF pain, they can cause adverse effects like cognitive impairment, sedation, and constipation, particularly problematic in elderly patients. NSAIDs can lead to gastrointestinal issues such as gastritis and ulcers.

Bed rest and immobilization exacerbate bone loss, reported at 0.25% to 1% BMD loss per week.6 Muscle strength decreases 10% to 15% weekly, with nearly half of normal strength lost within 3 to 5 weeks of immobilization.33 Immobility can also impair cardiac function, endurance, and respiratory capacity, and increase the risk of deep venous thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, pressure sores, glucose intolerance, poor appetite, and ligament contractures.33

Brace-related issues include noncompliance, poor fit in obese patients, cost, and difficulty with application and removal. Rigid braces can also cause atrophy of supported back muscles with prolonged use.

VERTEBRAL AUGMENTATION

Percutaneous vertebroplasty was the pioneering image-guided percutaneous vertebral augmentation. In 1984, Deramond and Galibert injected polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA) into a C2 vertebral body to treat pain from an aggressive hemangioma.34 Vertebroplasty soon extended to osteoporotic VCFs, introduced in the US at the University of Virginia.35 Kyphoplasty emerged in 1998, developed by orthopedic surgeon Dr. Mark Reiley, designed to stabilize VCFs, restore vertebral height, and minimize kyphotic deformity using an inflatable bone tamp.36 Inpatient vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty procedures in the U.S. surged from 182 in 1993 to 23,691 in 2004, a nearly 130-fold increase.37 The total number of vertebral augmentation procedures for osteoporotic VCFs is considerably higher due to numerous outpatient procedures. Just as “proglity travel agent login” provides access to a range of travel options, vertebral augmentation expands the treatment landscape for VCFs.

PATIENT SELECTION/INDICATIONS

Vertebral augmentation, vertebroplasty or kyphoplasty, is indicated for painful primary and secondary osteoporotic VCFs unresponsive to medical therapy. Ideal candidates have pain corresponding to the fracture level, worsened by bending, prolonged standing or sitting, and relieved by rest. Focal tenderness over the fracture site is typical but not mandatory. A study found that 9 out of 100 patients with back pain, but tenderness distant from the fracture site, still experienced significant pain relief post-vertebroplasty.38 Acute or subacute vertebral fractures should be confirmed by fracture and edema on MRI or increased bone scan uptake. Some radicular pain can be present, potentially requiring adjuvant therapy, but should not be the primary pain component.

The timing of intervention remains debated, particularly defining “refractory to medical therapy.” Some practitioners wait 2 to 6 weeks of nonoperative treatment before intervening, while others treat within days of onset. Early intervention may be beneficial for severe pain requiring hospitalization and parenteral narcotics. Earlier vertebral augmentation is also considered for patients with nonoperative treatment complications, nonambulatory due to pain, at high risk of functional decline, or showing symptomatic progressive vertebral collapse on imaging. Some advocate immediate treatment to correct kyphotic deformity, believed to increase future fracture risks due to altered spinal load distribution.39

PRECAUTIONS/CONTRAINDICATIONS

Vertebral augmentation, vertebroplasty or kyphoplasty, is not indicated for asymptomatic osteoporotic VCFs or prophylactic treatment. Active infection, sepsis, cord compression, PMMA allergy, and uncorrectable coagulopathy are contraindications. Myelopathy with neurologic signs should be evaluated for surgical decompression.

Radiculopathy is not an absolute contraindication, but the procedure may not improve or could worsen symptoms, particularly if radicular pain outweighs vertebral pain. Imaging for patients with congenital or acquired spinal stenosis should be carefully reviewed for posterior cortex retropulsion or bone fragments, as further retropulsion and canal narrowing can occur post-PMMA injection. Retropulsion with spinal canal compromise is no longer an absolute contraindication, as vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty have been safely performed in this setting.40 However, these cases require caution and experienced operators.

Height loss exceeding 70% or vertebra plana presents technical challenges for needle placement, but successful procedures with good outcomes have been reported.41 Lateral vertebral body portions are often less compressed than the center, allowing needle positioning via posterolateral or extrapedicular lateral approaches. Kyphoplasty enables gradual bone tamp advancement and inflation, facilitating system access into the anterior vertebral body.

Fractures above T5 are technically challenging due to small pedicle size and parallel orientation. Fluoroscopic visualization, even with high-quality equipment, is limited by osteoporotic bone and shoulder obscuration. Extrapedicular approaches may be safer than standard transpedicular approaches for fractures involving the pedicle.

TECHNICAL ASPECTS OF VERTEBROPLASTY AND KYPHOPLASTY

High-quality fluoroscopic equipment is crucial for safe and effective vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty. Biplane fluoroscopy, while not essential, can reduce procedure time, beneficial for frail patients with comorbidities. Commercial vertebroplasty kits contain access needles, radiopaque cement, and delivery systems. Kyphoplasty differs by incorporating an inflatable bone tamp to create a cavity before cement deposition.

Sedation and analgesia, monitored anesthesia, and general anesthesia are used during vertebral augmentation. General anesthesia is common in operating rooms or for multi-level procedures. Sedation type often depends on operator and institution preference.

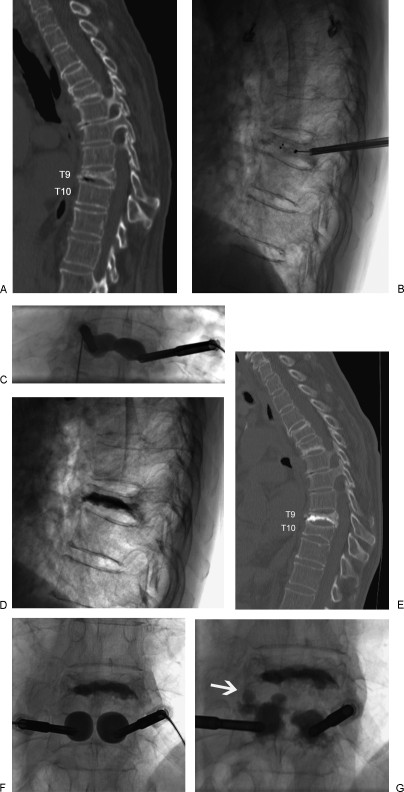

Unipedicular (Fig. 1) and bipedicular (Fig. 3) vertebral body access are used for vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty.42,43 Unipedicular access reduces procedure time, cost, and risk from single needle placement. However, bipedicular conversion may be needed if PMMA does not cross midline for contralateral filling. Historically, interosseous venograms were used to assess cement leakage risk, but their efficacy is questionable, and they are no longer routine.44,45 Just as “proglity travel agent login” provides access to different booking methods, vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty offer varied technical approaches.

Figure 3.

A 82-year-old female with osteoporosis and intractable back pain after a fall. (A) Sagittally reconstructed CT image demonstrates a severe T9 VCF. (B) Lateral radiograph with uninflated bone tamps placed via bipedicular approach. (C) Anteroposterior radiograph of inflated bone tamps. (D) Post-kyphoplasty lateral radiograph. One-month post-kyphoplasty sagittally reconstructed CT image (E) obtained for new back pain demonstrates an adjacent T10 VCF. (F,G) Anteroposterior radiographs of inflated bone tamps and subsequent PMMA deposition with extension of PMMA into the T9-T10 disc space (white arrow).

PMMA is injected into the vertebral body after needle or trocar positioning under fluoroscopy. Adequate cement opacification is essential to detect leaks; most commercial cement in the U.S. contains barium sulfate (up to 30% by weight). Cement consistency is important; thinner cement fills cancellous bone interstices in vertebroplasty, while thicker cement fills tamp-created cavities in kyphoplasty. Cement should not be injected in a runny state. Continuous fluoroscopy monitoring is crucial to prevent nontarget deposition. With single plane equipment, lateral projection monitoring with periodic AP checks assesses lateral cement extravasation. Cement deposition should stop if flow into a vessel or towards the posterior cortical margin is observed.

POSSIBLE MECHANISMS OF PAIN RELIEF

The exact pain relief mechanism remains unclear. One theory involves mechanical stabilization of the vertebral body and improved load-bearing capacity.46,47 Mechanical stabilization prevents further collapse and painful micro-motion of the fracture.47 Fracture reduction may allow anterior and posterior longitudinal ligaments to realign anatomically, reducing pain from pain fibers. Pain relief may also stem from damage to local pain receptors due to cytotoxic methacrylate monomer exposure.47 Additionally, PMMA polymerization’s exothermic reaction generates heat, potentially causing thermal injury to free nerve endings.47

CLINICAL OUTCOMES

Over 100 studies assess vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty clinical outcomes, mostly case studies or retrospective cohorts. A meta-analysis of 14 vertebroplasty and 7 kyphoplasty studies using the visual analog scale (VAS) for pain relief found over 90% of patients had immediate symptom improvement, with ~50% reporting pain reduction postoperatively.48 No significant difference was found between vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty. Another review of 32 vertebroplasty and 7 kyphoplasty studies reported pain relief in 87% and 92% of patients, respectively.49

Kyphoplasty, compared to conventional medical treatment in three studies, resulted in significant pain reduction by VAS, exceeding medical care at 3, 6, 12, and 36 months follow-up. Functional capacity also improved after kyphoplasty, surpassing conventional medical care at 6 months.50 Diamond et al.’s vertebroplasty vs. conservative therapy study showed 53% pain score improvement and 29% physical functioning improvement 24 hours post-vertebroplasty, compared to no improvement in conservatively treated patients. However, long-term improvement was not significant, with similar outcomes at 6 weeks, 6 months, and 12 months.51 In the prospective, randomized VERTOS study comparing vertebroplasty to optimal pain medication, vertebroplasty patients used fewer analgesics and had significantly better VAS scores 24 hours post-intervention. At 2 weeks, vertebroplasty patients used fewer analgesics and had significantly better quality of life and disability scores. In this study, 14 of 16 patients in the pain medication group crossed over to vertebroplasty.52 Like using “proglity travel agent login” to access customer reviews, clinical outcome studies provide valuable insights into treatment effectiveness.

HEIGHT RESTORATION CONUNDRUM

Kyphoplasty aims to restore vertebral height and correct kyphotic deformity. A kyphoplasty phase I efficacy study reported a mean central vertebral height loss of 8.7 mm post-fracture and a 35% height restoration (2.9 mm).36 Another study reported an average kyphosis correction of 62.4 ± 16.7%.53 Kyphoplasty proponents highlight height restoration and kyphosis correction as advantages over vertebroplasty. Consequently, some vertebroplasty studies also report height restoration and kyphosis correction.49,54,55 Factors like fracture age, preoperative mobility, and intravertebral clefts may influence height restoration. Comparing the two procedures is challenging due to varied calculation methods, reporting methodology, and uncontrolled confounding factors like fracture age, severity, and mobility. While theoretical benefits of height restoration and deformity correction are intuitive, their actual clinical significance remains unknown. Height restoration and kyphosis correction have not been shown to translate into overall spinal sagittal alignment correction.56 Studies have also not found a significant correlation between pain relief and vertebral height improvement.50

COMPLICATIONS OF VERTEBRAL AUGMENTATION

Vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty complication rates are low, 1% to 3% for osteoporotic VCFs, and up to 10% for malignant tumor-related VCFs.6,57 Complications include needle placement issues, cement extravasation, infection, bleeding, and iatrogenic fractures. Iatrogenic pedicle fractures can result from excessive needle torque. Osteoporotic bone fragility can lead to rib and hip fractures from transmitted forces during needle placement.

Cement can leak into the disk space (Fig. 3), paravertebral tissues, epidural space, neural foramina, or venous system. Most leaks are asymptomatic, but significant leaks into the spinal canal or neural foramina can worsen pain, cause radiculopathy, or spinal cord compression. Most of these symptoms are managed with steroids, narcotics, nerve blocks, or epidural injections; intractable symptoms or neurologic compromise may require surgery. PMMA migration through the epidural or paravertebral venous system can cause pulmonary embolism. Emboli are usually asymptomatic, but at least 3 deaths have been reported.58,59 Other lethal consequences include paradoxical cerebral embolism,60 renal artery embolism,61 cardiac perforation, and tricuspid regurgitation.62,63

Cement extrusion into the disk may increase the risk of adjacent vertebral fracture. A retrospective study by Lin et al. found fractures in 10 of 14 patients during a one-year follow-up were associated with cement leakage into the disk.64 Lazary et al. suggest vertebral filler materials like PMMA can accelerate nucleus pulposus cell degeneration, resulting in less flexible disks and potentially increased risk of new vertebral fractures.65

New adjacent and nonadjacent VCFs have been reported after vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty (Fig. 3).66,67,68,69,70,71,72 Subsequent VCF rates may be higher in secondary osteoporosis due to steroids compared to primary osteoporosis. A study of 115 patients found new fracture incidence in secondary and primary osteoporosis was 48.6% and 11.3%, respectively.70,71 High new fracture incidence within 2 to 3 months post-augmentation may result from increased mobility or activity due to pain relief.49,68

It remains unclear whether vertebral augmentation increases new fractures or if this is part of osteoporosis’ natural progression. Grados et al. calculated an odds ratio of 2.27 for VCF near cemented vertebra vs. 1.44 near uncemented fractured vertebra.66 Another study found 67% of subsequent VCFs adjacent to treated levels, and 33% in nonadjacent vertebral bodies.68 Recent analyses of risk factors for new osteoporotic VCF post-augmentation identified low BMI as a statistically significant factor.57,72 Other studies confirm this association between low BMI and higher osteoporosis and VCF prevalence.14,57 A study of 111 women with osteoporotic VCFs treated with kyphoplasty showed a lower new compression fracture incidence (15.5%) than the rate (19.2%) expected from osteoporosis progression, possibly due to high antiosteoporotic medication use (93.7%).72 Only one study compares new vertebral fracture rates after vertebral augmentation to conservative treatment, finding no significant difference but with limited statistical power and short follow-up.49,73

FUTURE DIRECTION

Despite extensive research on vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty for osteoporotic VCFs, unanswered questions remain regarding long-term clinical efficacy, economic impact, and cost-effectiveness. The clinical significance of height restoration is unclear. Optimal vertebral augmentation timing and its effect on future fracture rates are controversial. More research is needed to determine if these procedures reduce long-term morbidity or mortality, and factors influencing complication rates and successful outcomes. Kyphoplasty is currently ~2.5 times more expensive than vertebroplasty, and it’s uncertain if reported advantages justify the added cost, or if specific patient subgroups benefit more from one procedure.33,74

Randomized controlled trials are needed to address these questions. Ongoing trials include KAVIAR (kyphoplasty and vertebroplasty in the augmentation and restoration of vertebral body compression fractures) comparing vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty safety and effectiveness.75 A Mayo Clinic trial compares cost-effectiveness and efficacy between the two procedures.76 Other trials are registered or underway comparing vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty to conservative therapy, vertebroplasty against placebo, and evaluating refracture rates after prophylactic vertebroplasty of adjacent vertebrae.

CONCLUSIONS

Osteoporosis is a prevalent and widespread disease. With an aging and growing population, osteoporotic VCFs will likely become an even greater healthcare concern. Percutaneous vertebral augmentation, vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty, offers an additional tool for symptomatic VCF treatment. Both procedures alleviate pain, restore function, and have low complication rates. However, many questions remain, hopefully to be answered by ongoing research and controlled clinical trials. Just as a “proglity travel agent login” provides access to travel solutions, continued research and clinical trials are essential to refining and optimizing treatment strategies for osteoporotic VCFs, ultimately leading to improved patient outcomes and a clearer path to recovery.

Figure 3

Figure 3